Gregor Mendel knew how to keep things simple. In Mendel's work on pea plants, each gene came in just two different versions, or alleles, and these alleles had a nice, clear-cut dominance relationship (with the dominant allele fully overriding the recessive allele to determine the plant's appearance).

Today, we know that not all alleles behave quite as straightforwardly as in Mendel’s experiments. For example, in real life:

- Allele pairs may have a variety of dominance relationships (that is, one allele of the pair may not completely “hide” the other in the heterozygote).

- There are often many different alleles of a gene in a population.

In these cases, an organism's genotype, or set of alleles, still determines itsphenotype, or observable features. However, a variety of alleles may interact with one another in different ways to specify phenotype.

As a side note, we're probably lucky that Mendel's pea genes didn't show these complexities. If they had, it’s possible that Mendel would not have understood his results, and wouldn't have figured out the core principles of inheritance—which are key in helping us understand the special cases!

Incomplete dominance

Mendel’s results were groundbreaking partly because they contradicted the (then-popular) idea that parents' traits were permanently blended in their offspring. In some cases, however, the phenotype of a heterozygous organismcan actually be a blend between the phenotypes of its homozygous parents.

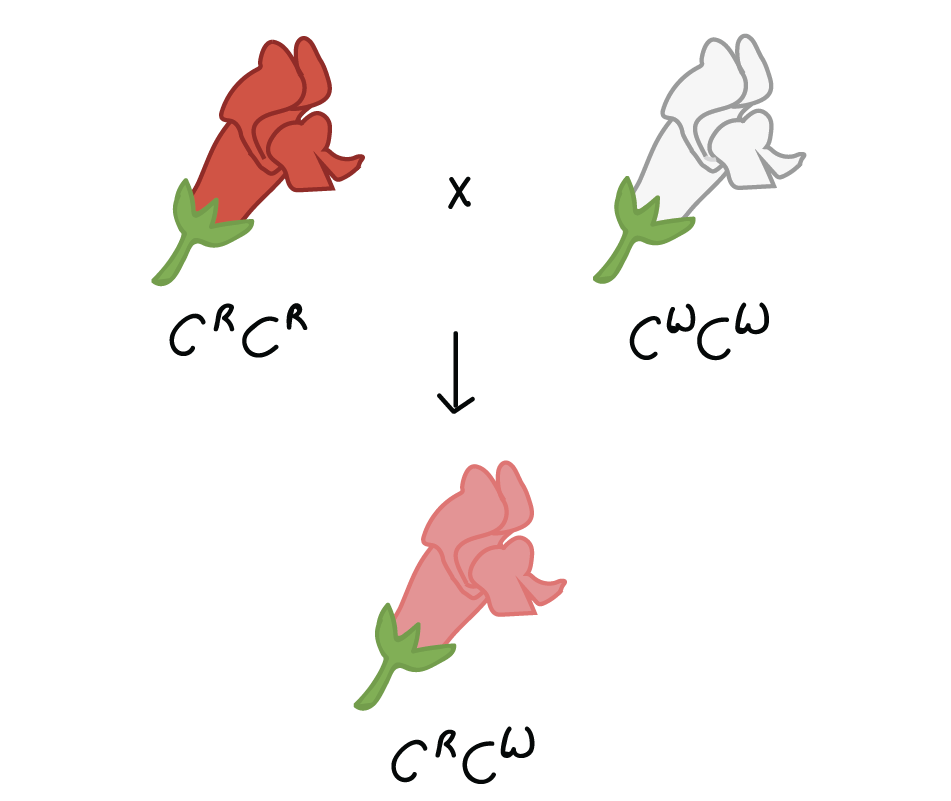

For example, in the snapdragon,Antirrhinum majus, a cross between a homozygous white-flowered plant (C, start superscript, W, end superscript, C, start superscript, W, end superscript) and a homozygous red-flowered plant (C, start superscript, R, end superscript, C, start superscript, R, end superscript) will produce offspring with pink flowers (C, start superscript, R, end superscript, C, start superscript, W, end superscript). This type of relationship between alleles, with a heterozygote phenotype intermediate between the two homozygote phenotypes, is calledincomplete dominance.

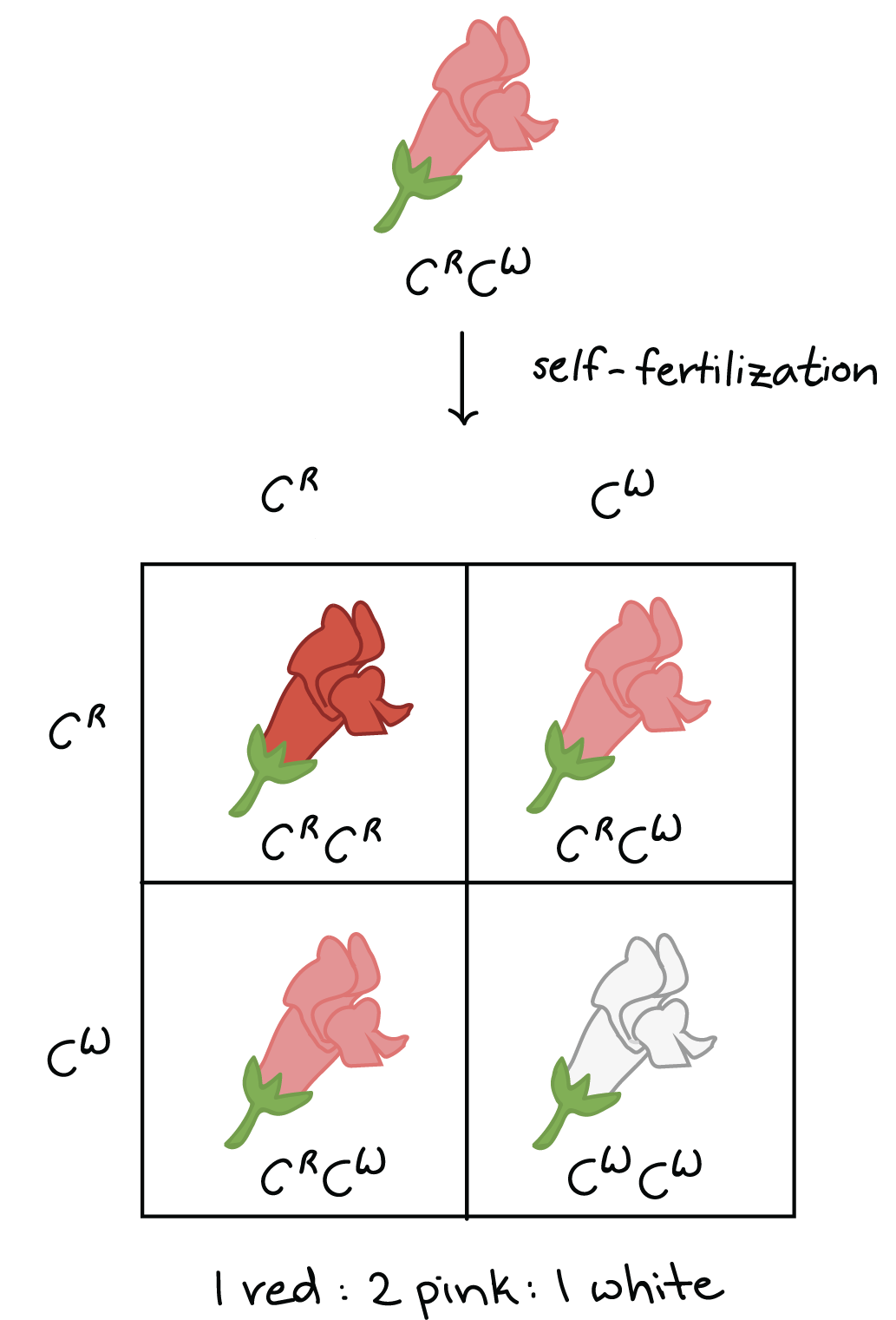

We can still use Mendel's model to predict the results of crosses for alleles that show incomplete dominance. For example, self-fertilization of a pink plant would produce a genotype ratio of 1C, start superscript, R, end superscript, C, start superscript, R, end superscript colon 2 C, start superscript, R, end superscript, C, start superscript, W, end superscript colon 1 C, start superscript, W, end superscript, C, start superscript, W, end superscript and a phenotype ratio of 1, colon, 2, colon, 1red:pink:white. Alleles are still inherited according to Mendel's basic rules, even when they show incomplete dominance.

Codominance

Closely related to incomplete dominance is codominance, in which both alleles are simultaneously expressed in the heterozygote.

We can see an example of codominance in the MN blood groups of humans (less famous than the ABO blood groups, but still important!). A person's MN blood type is determined by his or her alleles of a certain gene. An L, start superscript, M, end superscript allele specifies production of an M marker displayed on the surface of red blood cells, while anL, start superscript, N, end superscript allele specifies production of a slighly different N marker.

Homozygotes (L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, M, end superscript and L, start superscript, N, end superscript, L, start superscript, N, end superscript) have only M or an N markers, respectively, on the surface of their red blood cells. However, heterozygotes (L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, N, end superscript) have both types of markers in equal numbers on the cell surface.

As for incomplete dominance, we can still use Mendel's rules to predict inheritance of codominant alleles. For example, if two people with L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, N, end superscript genotypes had children, we would expect to see M, MN, and N blood types and L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, M, end superscript, L, start superscript, N, end superscript, and L, start superscript, N, end superscript, L, start superscript, N, end superscript genotypes in their children in a 1, colon, 2, colon, 1 ratio (if they had enough children for us to determine ratios accurately!)

Multiple alleles

Mendel's work suggested that just two alleles existed for each gene. Today, we know that's not always, or even usually, the case! Although individual humans (and all diploid organisms) can only have two alleles for a given gene, multiple alleles may exist in a population level, and different individuals in the population may have different pairs of these alleles.

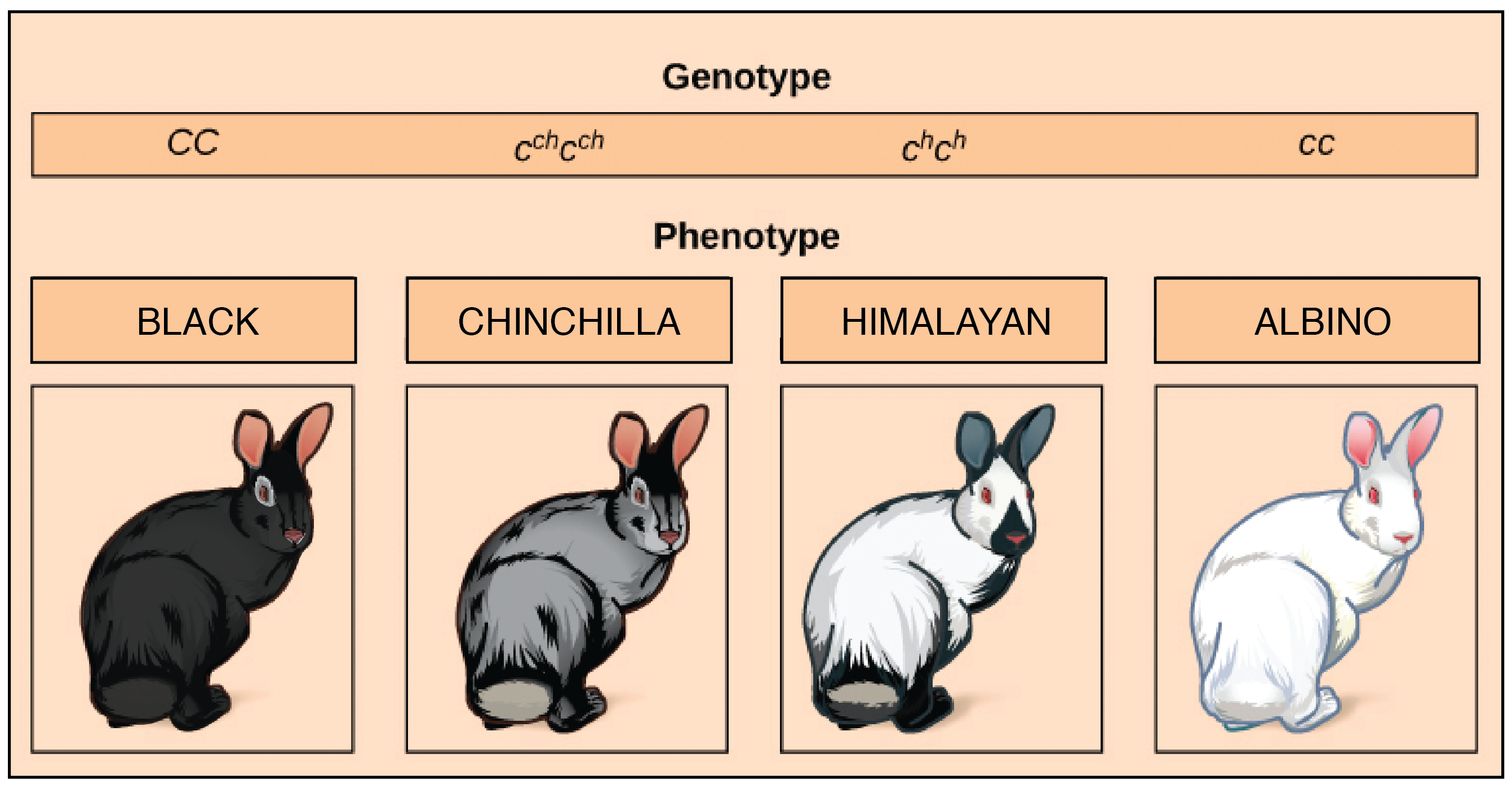

As an example, let’s consider a gene that specifies coat color in rabbits, called theC gene. The C gene comes in four common alleles: C, c, start superscript, c, h, end superscript, c, start superscript, h, end superscript, and c:

- A C, C rabbit has black or brown fur

- A c, start superscript, c, h, end superscriptc, start superscript, c, h, end superscript rabbit has chinchilla coloration (grayish fur).

- A c, start superscript, h, end superscript, c, start superscript, h, end superscript rabbit has Himalayan (color-point) patterning, with a white body and dark ears, face, feet, and tail

- A c, c rabbit is albino, with a pure white coat.

Multiple alleles makes for many possible dominance relationships. In this case, the black C allele is completely dominant to all the others; the chinchilla c, start superscript, c, h, end superscript allele is incompletely dominant to the Himalayanc, start superscript, h, end superscript and albino c alleles; and the Himalayan c, start superscript, h, end superscript allele is completely dominant to the albino c allele.

Rabbit breeders figured out these relationships by crossing different rabbits of different genotypes and observing the phenotypes of the heterozygous kits (baby bunnies).

No comments:

Post a Comment